My life is finally slowing down after a number of weeks of events, diabetes awareness "stuff" and children being off school for mid term break. I have so many blogs posts in my head and no time to write them. But soon...

In the meantime, while I was fast asleep, my husband had a moment of inspiration about living life with type 1 diabetes and what common human experience might come close to describing the type 1 diabetes experience? Yes, there are a lot of questions to ask about why I was asleep and he wasn't but not for publishing online ;-)

So here is a guest post from my hubby.

Gráinne was away at a conference recently, presenting the "patient experience" to a group of 100 almost entirely healthcare professionals. She came home the first evening very excited by not only how well her talk was received, but the general tone of the conference in general.

I'm sure she will fill in details about the conference in a separate post, but I wanted to write a quick blurb about something that struck me at 3am (don't ask): how does anybody gain insight into the life of a person with type 1 diabetes in an effort to build empathy?

The intellectual approach of explaining all the things one does to manage type 1 is important but somehow inadequate. Living with (and sleeping next to) a person with diabetes (PWD) can give you some insights, and loving a PWD to the extent where you have some of the same fears and worries they do at a very emotional level yields a whole new level of insights.

But such experiences are hard-earned and not wholly practical. To start with, I'll take issue with others sleeping next to my wife on anything other than an exceptional basis :)

What struck me is there is a very common human experience that might come close to describing the type 1 diabetes experience: parenthood. I may not have diabetes, but I live with somebody who does. And...I am a parent of two pretty amazing kids.

What can parenthood do to help build empathy for those living with type 1? Let me share a partial list:

1. Say goodbye to a reliable full night of uninterrupted sleep.

Even in her pre-CGM days, Gráinne would wake up in the middle of the night not feeling right. Her sugars could be high or they could be low, or she could just be coming down with something. Regardless she had to check her sugars and then decide how to react to the information.

I wouldn't say it's quite like having a newborn baby, but it's pretty close to having a 6 month old baby who can't reliably settle. But without the option of seeing if the baby will be able to settle herself...and without the possibility that the 6 month old baby will grow out of it.

A new parent is often desperate for a manual on "how to be a good parent." What you learn as a parent is that every child is unique and has their own set of needs. You just need to figure out what works best for the child in front of you at the time. And of course what works for a two year old is not what works for a twelve year old: the "rulebook" for parenting is forever changing.

Type 1 seems to work in much the same way. There are so many variables in life that what worked for you last week may not work for you this week. You just take on whatever challenges type 1 throws at you, and deal with them in the best way your sleep-deprived, hypo-affected brain can manage.

We've all as parents done things that we regretted. Maybe it was giving a punishment that was in retrospect overly harsh. Or maybe we're worried that we're being too lenient, or not helping our child learn lessons the hard way because we're spoon-feeding them the answers. Or maybe our child is struggling in school, or struggling socially, or trying really hard in a sport that they love but are lacking the skills to be really good at...and we feel somehow responsible for this and guilty that we're failing them as parents.

If you have type 1, guilt about "not managing your diabetes" seems to be there. Always. That bit of extra chocolate you had because it looked nice? Unless you accounted for it perfectly (and see point 2: you probably didn't account for it perfectly because there is no rulebook), you're probably going to see the result of that "indiscretion" in your blood sugars. Not getting the HbA1c result you hoped for? More guilt and self-loathing.

4. Low-grade worry.

As parents, we often worry about our children's future. Some of these things are those over which we have control (and feel guilty about doing "wrong"). Others are longer-term things over which we have no real control: is the planet going to be habitable by the time my grandchildren are born? And every so often, we think about our own mortality: what would happen to our children if Gráinne and I were to die unexpectedly?

These aren't necessarily things that keep us as parents up at night (those are more the "guilt" topics!), but they are the things that can weigh on the mind of a person with type 1. Mortality is a much more real presence in the life of someone with type 1: the very medication that is needed to keep you alive can also kill you (or worse).

5. Lots of "outside" advice

New parents (and experienced parents!) are often awash in advice, both solicited and unsolicited. It is advice commonly wrapped in "you should" and "never" and "always"...very emotionally charged terms.

Have you ever talked to a mother who wants to breastfeed but wasn't able to make it work for whatever reason? Feeding her baby with a bottle can bring on a whole world of emotions with that simple act of providing nourishment to her child, and that's before the very "helpful" commentary from some well-meaning individual: "breast is best!"

The world of diabetes management is awash in advice, much of it from medical experts and some of it from crackpot experts who read an article about "how cinnamon can cure diabetes" or some other such thing. But much with parenting, what a PWD must do is learn to figure out what advice is helpful to them and use that, whilst figuring out how to deflect and ignore advice that does not.

There are more parallels between "parenting" and "managing type 1 diabetes," but this has hopefully given a taster based on my perspectives as a "diabetes insider-but-outsider."

There's one thing, however, that is DRAMATICALLY DIFFERENT FROM BEING A PARENT. Parents do not have any sort of scorecard. I mean okay, if you have killed your child violently are severely neglecting them to the point their health is in danger, you've clearly failed as a parent...but beyond that parenting is pretty much a "pass" sort of proposition...our children grow up, leave the home, and succeed (or fail) largely on their own effort, merits and socioeconomic position.

But in the world of diabetes...there are all sorts of numbers. The most notable one has been mentioned here a few times: HbA1c, or the "time-weighted average blood sugar over the past three months." Doctors have historically focused on this number which is about as useful for an individual as the Body Mass Index (which is to say: not terribly useful).

With the advent of CGM and FGM technologies, they're now starting to focus on "time in range" which is arguably a better indicator of overall diabetes management and overall health, but it also somehow fails to account for the fact that there are just so many factors over which a PWD has no control.

That's the thing: most PWD who are armed with the best of knowledge, tools, and medicines will struggle to achieve their target HbA1c or time in range.

Imagine if we were to devise a "parenting index" for each and every parent, as a value between 0 and 100, and we set it up in such a way that it's pretty much impossible to get a 100, or even an 80. Why? Because your children have a mind of their own, you can't control them 100% of the time, there are people other than you influencing their lives, and you're human so will make mistakes.

But you as a parent know that "100" is the best possible score, and so you try really really hard to get 100...you're trying to do everything the experts say you should be doing, you're spending lots of money and time to achieve perfection and love your child like no parent has ever loved their child. But year in and year out, you struggle to get a score over 60. Your best ever score was a 77.

And now ask yourself: Are you a failure as a parent?

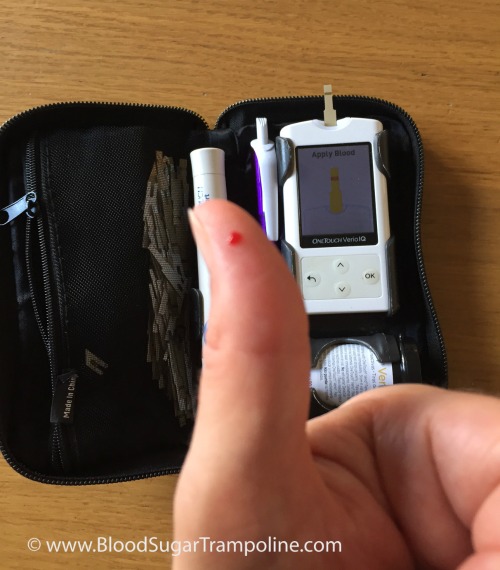

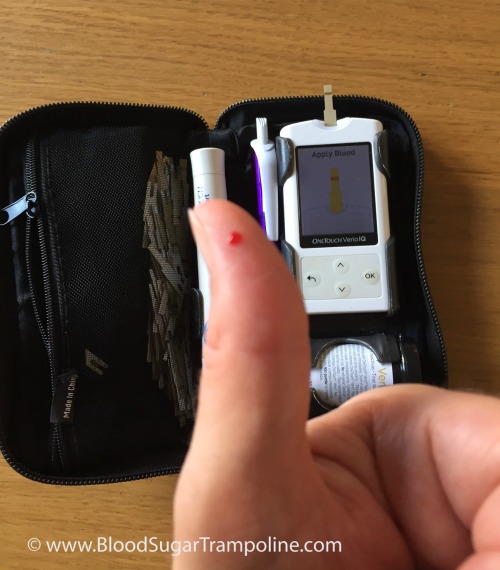

Before breakfast, I checked my levels again; they were in target, so I took my insulin for my regular weekend breakfast of tea and toast also known as 40g of carbs and then ate it.

Before breakfast, I checked my levels again; they were in target, so I took my insulin for my regular weekend breakfast of tea and toast also known as 40g of carbs and then ate it.