I realised last year that in all the blog posts I’d done these last 13 years, I have never shared my diagnosis story, so here it goes.

My diabetes diagnosis is not unique; many of my friends with diabetes share similar experiences; however, some people end up very ill and may have spent time in intensive care units in hospitals. Thankfully this was not the case for me, but I did feel like I was dying.

Before Diagnosis

I turned twenty in December 1992; I was a student living away from home since I did my Leaving Cert exams at seventeen. The previous September, after living with my uncle and his family since moving away from home, I moved into my own place for the first time. I was studying, working part-time, cooking for myself, food shopping, paying bills, all those grown-up things and loving it. Then my entire world was turned upside down and it took a number of years to find my confidence and feel safe in the world again.

My Symptoms

I can’t pinpoint when exactly the weight loss started, or the need to “wee” all the time, or the thirst became unquenchable, I do remember a series of instances where I thought “This is weird!” such as nights having finished my dinner and still feeling hungry. I also remember being out with a primary school friend in early February, and the skirt I wore was a bit looser than it usually was. Again, another delightful moment and nothing at all to be alarmed about.

My symptoms started in earnest about three or four weeks before I ended up in hospital. I was so hungry a lot of the time. At dinner, I would cook a modest meal, meat, veg and boiled potato and still be hungry, so I’d have a Weetabix or a slice of bread and butter but I would call a halt to the gluttony after a cup of tea and a digestive biscuit.

Then, I started to feel sleepy and thirsty more. During the last two weeks, those symptoms became more severe: the thirst was unquenchable, and I had a plastic one-litre bottle that I filled multiple times throughout the day. The only symptom that didn’t seem odd was the need to pee almost every hour. The extreme exhaustion was unbelievable: I felt that my body didn’t have the strength or energy to hold me upright: I couldn’t stand up for more than a couple of minutes without leaning or holding on to something, and I couldn’t sleep enough.

My massive weight loss was the last thing I noticed, I remember one morning when I was getting dressed and closing my jeans belt on the very last notch – I knew I had been losing weight, but this was the point where I thought, “this isn’t possible” and I convinced myself that the leather belt had stretched because that sounded more plausible than losing so much weight while eating everything in sight. My vision was a little blurry, so when I noticed my ribs and hips protruding in the mirror after my shower, I thought the shower steam was distorting my reflection.

For the first few weeks, I explained these unusual symptoms due to being run down because I was working late shifts at the fast food place four or five nights a week as well as attending classes during the day. I decided to take the week off college to rest but to still do my shifts to keep my income rolling in. I slept lots and lots, but I was still so exhausted. So tired that the thought of hauling myself out of an armchair to go to the bathroom, yet again, took all of my energy me. I didn’t have the energy to stay standing up, not even for a couple of minutes without leaning against something.

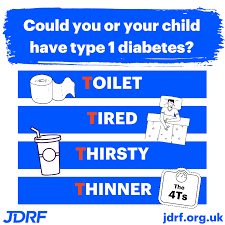

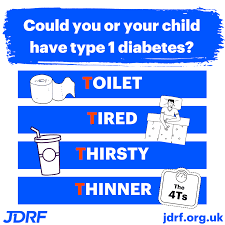

The 4 T’s of Diabetes: Tired, Thirsty, Thin and Toilet

Young people like me didn’t get sick unless it was something serious, right? I couldn’t eat enough, drink enough, pee enough or sleep enough; something was wrong, and it was time to find out.

When I went back to classes, I decided to seek out the help of one of my classmates, Marise, a former nurse, but I didn’t catch up with her until Friday. I told her how I was feeling and that a friend had mentioned diabetes the previous weekend and she could tell me what the symptoms were. This was 1993 before we had Dr Google or even the internet. She listed off the symptoms of insatiable thirst, trips to the toilet, excessive tiredness and weight loss. All I could say to her was that I had every one of them, to which she said that I should get to a hospital ASAP; she even offered to take me. But, as soon as I heard the word “hospital”, I already knew that if this was where I was going, I was going to be in one that was close to where my Mammy and Daddy could visit me. My mode of transport in those days was a bicycle, which is probably why I lasted so long without falling unconscious, and I hopped on that thing to get back to my house, pack a bag and call my mother to make a doctor's appointment before getting to the train station.

When I got to my house, I made a quick phone call home to ask my mother to collect me at the train station and to organise an appointment with our GP. My landlord happened to be in the house doing some DIY when I got there, and I must have looked like I was on death’s door because he offered to carry my bag to the bus for me, which I gladly accepted. By now, I was starting to feel nauseous. I hadn’t eaten anything since breakfast; it was now late afternoon, so I stopped at a shop to pick up something to eat. I only did this because I thought I should, and I picked up the first thing I saw, a Mars bar because sugar is good for people who feel faint, right, and affordable for students. I don’t even like Mars bars, and I absolutely did not feel like eating the damn thing. By the time I made it to the train station, I’d missed the early train, so had to hang around for the next one. I made an attempt to eat the Mars bar because everyone knows that it’s not healthy to go so long without eating. Thank God I didn’t finish it!

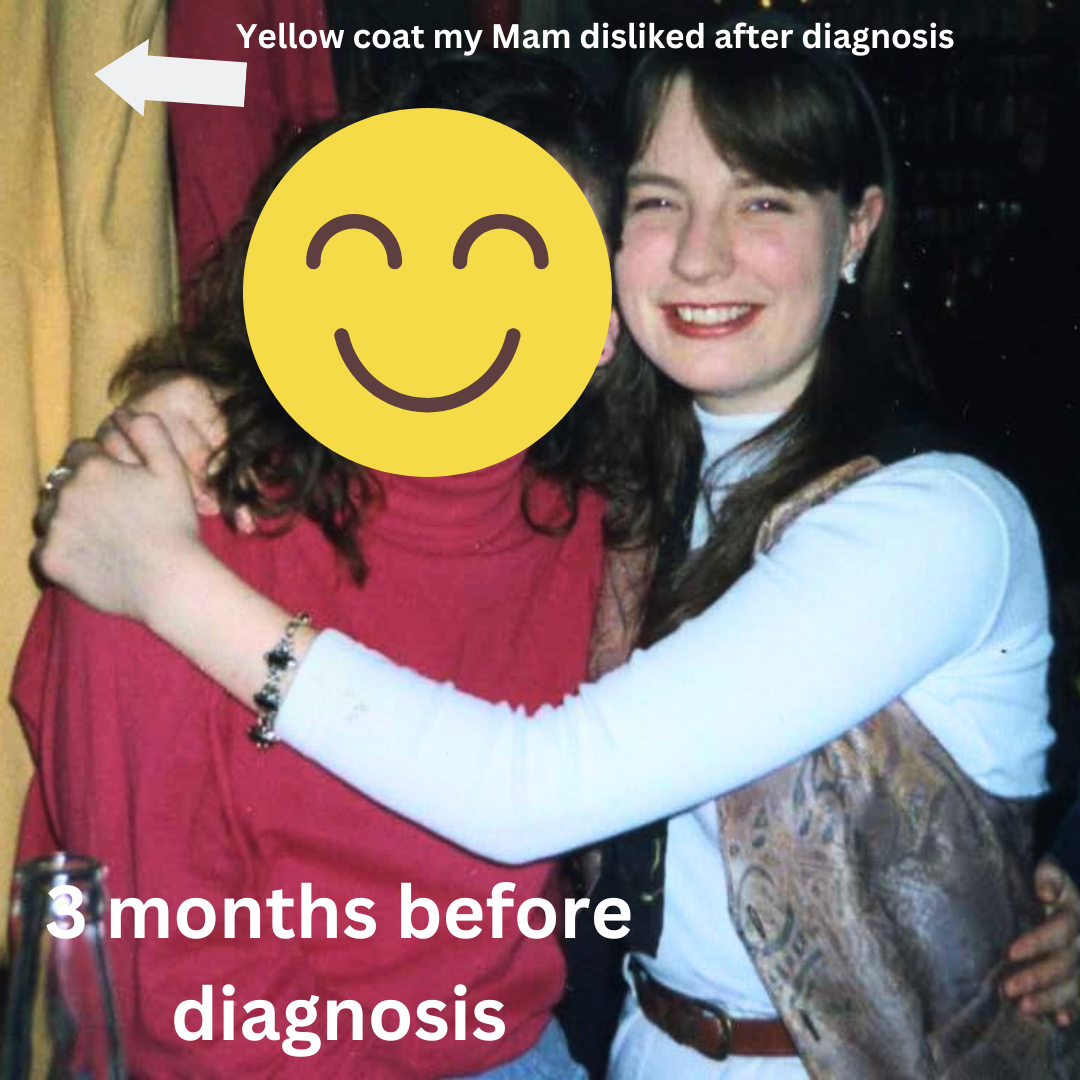

You know everything was on my side that day, the landlord being around, the train journey only lasting an hour (it could have been a lot longer on a busy Friday evening). When I got off the train, my mother got such a shock when she saw me, and her first words were, “I made the appointment for tomorrow, but I think we’ll just go straight in”. She reminds me to this day that I wore a mustard yellow winter coat that she hated seeing afterwards because of how I looked that day.

Getting to Hospital

From this point onwards, I handed myself over to my mother to take care of me; I was barely able to walk or talk. The journey to the doctor’s office from Tullamore train station was a 30-minute drive; my mam decided that we should stop halfway at my Aunt’s house so she could call ahead to the doctor because it was after surgery hours. I told her that was great because I could use the bathroom again. My mother said that my Uncle Pat was taken aback when he set eyes on me. He’s the type that takes everything in his stride, very easy-going; his reaction was a little worrying. I don’t really remember, at this point, I was barely hanging in there, and I was relieved that I had my Mammy taking care of everything. After I used the bathroom in my Aunt’s house, my mam and Uncle Pat found one of those empty brown tablet bottles, and she told me that the doctor had asked that we bring a urine sample. I think she was a bit surprised when I said, “Not a problem,” and turned on my exhausted heels to head back to the bathroom to fill it to the brim.

The doctor was waiting for us, and we went straight into his office. A quick dip of a stick in the wee, a nod to my mother who had given him a heads up on the diabetes thing, a note for A&E later, and we were off to Accident & Emergency or “Casualty” as it was known then. Now that I’ve had years to reflect on our journey from the train station in Tullamore to Birr to Ballinasloe only, to realise that we probably should have gone straight to the A&E department in Tullamore hospital but we knew nothing back then.

At this point, my mental and physical state was that of a vegetable: I was so, so, so tired, thirsty and feeling so sick. My parents’ house was en route to the hospital, and my practical mother knew I would need some things. I usually didn’t travel home with pyjamas or a toothbrush because I kept a set at my parent's house. She also needed my father for some moral support. I don’t remember if she called home when we were at my aunt’s, but she must have, at least to let my Dad know that we were going to be delayed. She had been shouldering this serious illness burden for at least an hour, and only she knew what kinds of worse-case scenarios were going through her head.

The A&E of the nineties was a very different world to our current times: we arrived, were seen very quickly and connected to a drip in what seemed like a few minutes. I don’t even remember if I saw the waiting room, but I’m sure my recall of this segment can’t be trusted. The first bag of fluid was pumped into me in 45 minutes; I do remember that because I realised I hadn’t needed to pee in all that time, and it was such a relief. The hours here were a bit of a blur, but I was horizontal and finally able to rest. By midnight, I was admitted, moved to a ward and not feeling so nauseous; plus, I hadn’t needed to go to the bathroom since arriving, which was bliss, even though I had a long way to go to recover yet. I slept the entire night without having to get up to go to the toilet.

Also, here's a little side note. I didn't know this until I recently asked my mother about some of the details about arriving at the local hospital emergency department. It was also the night Gay Byrne interviewed Annie Murphy on the Late Late Show, a significant piece of history for Ireland.

"You have diabetes, and you will have to inject insulin for the rest of your life”

You have Diabetes

It was the Friday before Palm Sunday when I was admitted to Portiuncula Hospital in Ballinasloe, Co. Galway. I looked up the date in later years to discover that it was April second.

My Dad and little sister, who was seven at the time, visited early the next morning. I was still so very tired, but I was feeling very human again; I didn’t have to run to the loo every 10 minutes, and I wasn’t knocking back the “corporation lemonade” (water) like it was going out of style. My Dad reported home that the difference in my appearance was huge in such a short time: I was a healthy colour again, and the change was so dramatic it could have been a miracle. They were so relieved.

Being in the hospital isn’t that bad on the weekends – loads of people came to visit me! I got loads of get well soon cards – all of which I kept. I was overwhelmed by the concern people expressed and felt guilty for causing so much worry. My visitors all asked me what I thought was wrong, and my answer was it was “suspected diabetes”, but we didn’t know for sure yet. My official diagnosis didn’t arrive until Monday morning. I have no recollection of being injected with insulin, but I’m sure this had to have been happening, and I’m sure that my blood glucose levels were being tested on a metre, but I don’t remember.

The Diagnosis Delivery

I remember the moment I was told I had diabetes like it was yesterday, but I don’t remember what came before or after those words. It was Monday before a doctor came to confirm what I had already thought I had. I vaguely remember him standing in front of a radiator, and maybe he was wearing a white doctor’s coat. I remember clearly he said, “You have diabetes, and you will have to inject insulin for the rest of your life”. I felt like someone had punched me in the stomach. Up until that point, I had been so relieved not to feel so deathly any more, but I hadn’t been thinking about a future; it just didn’t occur to me. Now I was thinking, what does the rest of my look like with diabetes? What does this mean? That night was the first of many that I cried myself to sleep where no one could see and for many nights afterwards while trying to adjust to this new normal and figure out why me.