I’ve been using an insulin pump for ten years and I have to say most of those ten years I never really had any site occlusions. That is until the last two years and since doing some research on Pump Site, or Occlusions as they are known by, I’ve come to realise that they happen quite often in the pump community.

My most recent Pump Needle Clog happened last week and completely wiped me out for the entire day.

Evening Pump Needle Changes

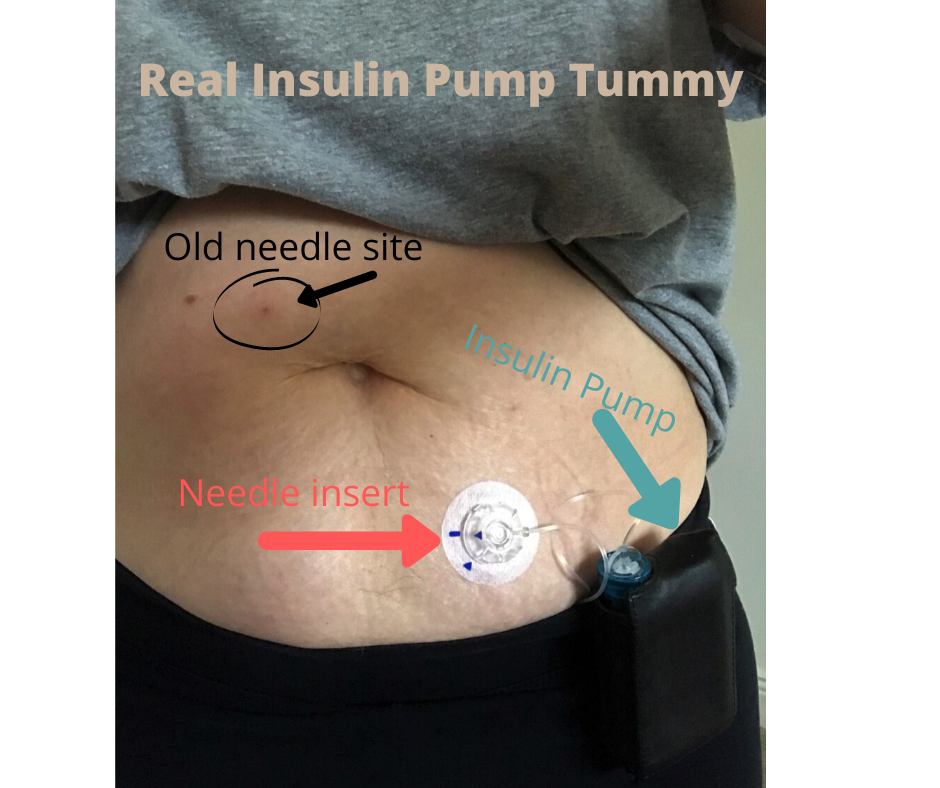

Using an insulin pump means that I have to change the thin plastic needle inserted under my skin every three days and also refill the insulin reservoir. This is one of the biggest benefits of an insulin pump: one needle every 3 days versus a needle every time I eat.

I make an informed decision to do my insulin pump needle changes before I go to bed for three reasons:

Convenience - it’s just too difficult to remember to do it at any other time of the day and I’m more likely to keep putting it off until bedtime anyway.

Sensor - I wear a glucose sensor too which will alert me if my readings go high or low

Less Variables in Play - there are less variables in play for me in the evening, such as not having any food since dinner so if my numbers are high it’s unlikely to be slow acting carbs. By doing my set changes at bedtime I figure out if it’s an occlusion at the cannula quicker and can correct it quicker before DKA happens.

Evening pump site changes are what work for me.

Recent Occlusion

I did my set change as usual before bed; I wasn’t sleep well but my glucose sensor alerted me to a blood sugar reading of 11.1 mmols/L at about midnight, which isn’t very usually so I hit snooze on the alarm believing that my DIY automated insulin delivery artificial pancreas system would address it.

A little while later my sensor alarmed again but this time my sugars were reading 15 mmols and I was really thirsty. I got up and went downstairs to check my levels on my meter as it was the first day of a new sensor to check for accuracy. The check confirmed the number and as I was already downstairs I grabbed my backup rapid acting insulin pen and took a 2 unit injection just to speed up recovery. I also gulped down a tall glass of water.

When I went back upstairs I replaced my cannula and began the waiting game. My levels did start to come down within a half an hour but it took until 4am to get back in range meaning that my CGM alarm kept going off from midnight until 4am, which I needed it to do so that I knew if I needed to give additional emergency insulin via my pen.

The result was that I was completely exhausted the next day.

A graph of my glucose profile during an insulin pump site clog

Previous Occlusion Experience

Previous to last week, I shared another occlusion experience on Twitter back in April where my sugar levels were high for only 4 hours but it was long enough and high enough to wake me up feeling nauseous.

This time, it took me a bit longer to figure out that it was a cannula problem but I did get up, do a finger stick to confirm high, changed out my pump site and fell back to bed. I was really thirsty but I couldn’t summon the strength to go downstairs for water. Thankfully, my husband woke up while I was rustling around in the dark for a fresh cannula and asked if I needed any water as I flopped back on the bed and went downstairs to get it for me. So grateful!

I know that this episode didn’t disrupt my sleep too terribly but I woke up feeling so wretched the next day and couldn’t wait to fall back into bed again at the end of it.

Research I found

I recently came across this piece on DiabetesMine: “Infusion sets remain “the weakest link” in insulin pump treatment, with as many as 60% of pump users reporting infusion set failures for a variety of reasons.”

This is so true and I really do hope that research can improve this.

“While past attempts at innovation in this area have faltered, new work is underway to disrupt traditional infusion technology, and give PWDs (people with diabetes) more insight into how well their current set is performing.”

And I would definitely agree with the Conclusions in this research paper: “Insulin Pump Occlusions: For Patients Who Have Been Around the (Infusion) Block”

Conclusions

“Insulin infusion pumps are an attractive technology for patients with diabetes; however, an occlusion of IIS can massively interfere with glycemic control and degrade patients’ confidence in this type of technology. Occlusions do occur frequently and often without an alarmed warning or this provided too late. There is a need to improve this situation by either: 1) proper education of patients with respect to IIS management; or 2) development of insulin pumps/IIS with robust predictive alarms for detection of occlusions and other technological solutions for the avoidance of occlusions.”

Please find solutions to occlusions!